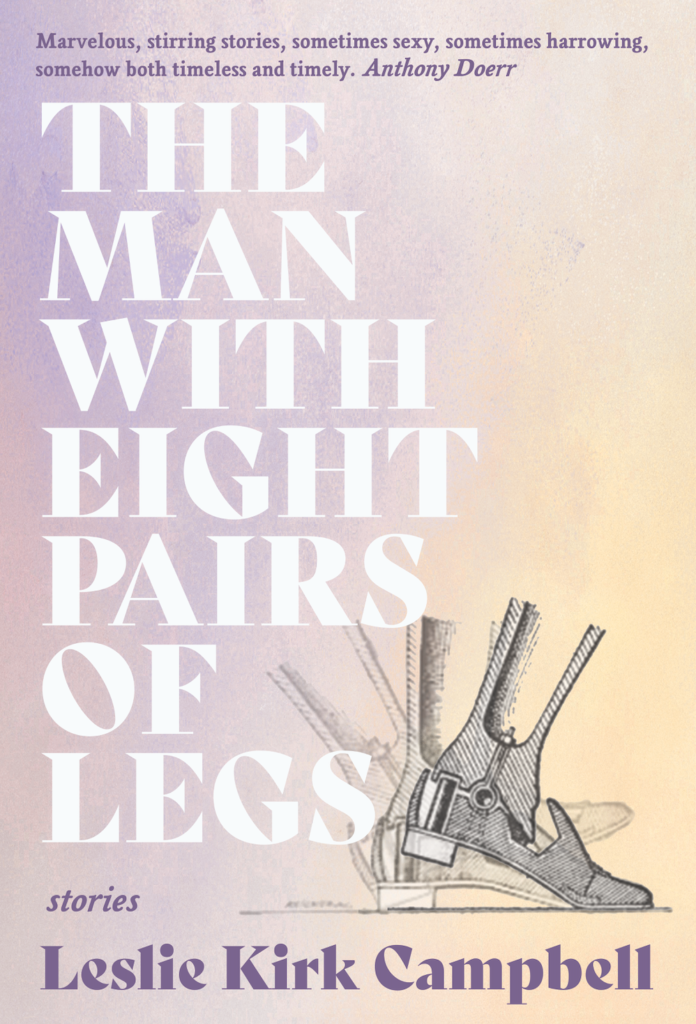

Where Did The Man with Eight Pairs of Legs Come From & How Did It Get Written?

HOW IT BEGAN:

This debut collection of short stories has been a long haul. One could say it started one summer day when I was nine years old in Capitola, California and wrote my first poem extolling the vastness, power, and sheer magnificence of the Pacific Ocean.

From that moment on, my love for the art of language never quit. I kept at it, writing intense, wild, well-received poems with Pulitzer prize-winning Kiowa author, Scott Momaday (House Made of Dawn) my senior year at Stanford…despite a demoralizing experience with a less generous writing teacher my freshman year. (More about that story in another post. Suffice it to say that this early experience of suppression versus nurture eventually led me to found a writing school, Ripe Fruit Writing – now the oldest non-institutional writing program in the San Francisco Bay Area – where I could champion every emerging writer’s unique content and voice.)

FROM POETRY TO FICTION:

After college, I got an MA in English Literature/Poetry from San Francisco State. It wasn’t until I had raised my two sons (10 years apart – I’ll hold off for now on the backstory) that I decided to try my hand at fiction. Hey, I could write. I had published a book of non-fiction: Journey into Motherhood (Riverhead). I had read, and analyzed, dozens of novels. Writing fiction, I thought, should be a no-brainer. Au contraire. No one told me that writing great fiction is so freaking hard! Fortunately, my learning curve skyrocketed during my two years getting an MFA in Fiction with Bennington’s low-residency Writing Seminars, which is where I fell in love with the poetry and density of the short story.

MEANWHILE, OVER THE YEARS, IDEAS FOR STORIES HAD BEEN PERCOLATING.

A long-married couple is playing a challenging word game. The husband, who is having an affair, is given six months to live but doesn’t tell his wife. What might happen between them? I wanted the entire story to take place on a single hot summer evening (Thunder in Illinois).

What if two transients to San Francisco, one a struggling artist and single mother from rural Kentucky, the other a gay man from New Orleans, were to form a complicated, symbiotic relationship during the AIDS epidemic of 1984 (Triptych)?

Sitting at my desk, I heard the electric saws – a woman was cutting down all the eucalyptus on her property. I felt that woman’s sorrow like a sack of stones in my gut, but what was she so sad about? I had to find out, and I did, when I wrote Tasmanians.

I had a dream I couldn’t get out of my head: a middle-class father gets entangled with the heroin addict squatting in the abandoned house next door (Nightlight).

I am a rape survivor, so I wasn’t surprised to discover two of my stories dealt with the violation of women’s bodies and the way society prepares girls for just such an outcome starting in middle school – if not before (Overture & City of Angels).

GRATITUDE: AT AN EARLY TURNING POINT IN MY WRITING LIFE, POET SCOTT MOMADAY WAS A SAVIOR.

But there were numerous others – colleagues and mentors – who were golden along the way, giving these stories close readings and helping bring them to fruition. A writer spends an inordinate amount of time in solitude, but no one accomplishes writing a book alone. It takes a village.

THROUGH COUNTLESS REVISIONS, EACH STORY FINALLY FOUND ITS WAY ONTO THE PAGE!

THE BOOK IS BORN:

Every writer writes what he/she/they need to write about, whether consciously or not. I have found this truth to be almost mythical. The potent creative seeds are primal. “Write as if you are dying,” says Annie Dillard (The Writing Life). Yes. I hadn’t planned on writing a book. But once I had a number of stories written, I was struck by the predominance of the human body as a focal point and realized that each of my stories was a kind of investigation into ways we hold our pasts, like inscriptions, on our skin – bruises, tracks, tattoos, scars – and invisibly through generations.

OMG! It has been as painful as it has been exultant. There are times when I wanted to give up. Martha Graham, the ground-breaking choreographer, once said, ‘You don’t even have to believe in yourself.” She was right. After a particularly difficult period, I learned that my writing faith runs even deeper than my belief in myself, or lack thereof. You just keep going. You keep creating. You write the stories you need to tell from your heart in whatever way your imagination guides you.

The author who chose my book for the Mary McCarthy Prize for Short Fiction, granted me solace when she wrote: