Location, Location, Location

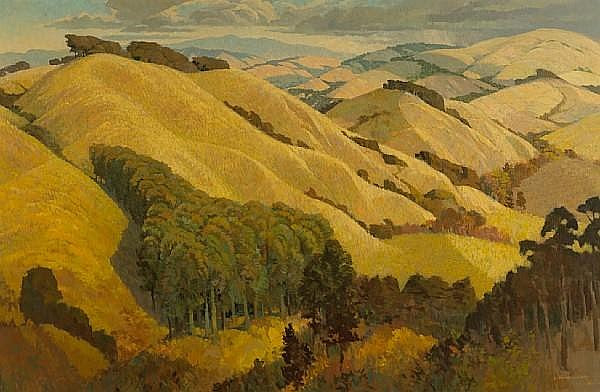

Mariam likes to get up before Cedric, just as the world is taking shape, and stroll in her nightgown and robe through their newly-built home on Novato Ridge – her Shangri-La. Oh, how they soothe her, these rolling hills that stretch north and west beyond the tidy housing development – like a pride of sleeping lions, she’s pointed out to Cedric – their tawny, muscular backs marked by scattered native oak and stands of towering eucalyptus.

(Tasmanians)

Nothing happens in a vacuum – except, my physicist husband tells me, tiny electromagnetic fluctuations due to photons. But here, in the visible world, people don’t just talk, or kiss or tie their shoes or light a candle in mid-air. Everything happens in a place. And every place has a smell, colors, textures, sounds, and visible light. Things happen in a particular room, in a specific town, on a particular stretch of sea, a certain street, a mountain – but not any mountain, one particular mountain, in fact, a specific trail on that mountain in a particular season at a particular time of day with all the correlating details. Place is never general. It is always particular. You can’t enter ‘houses’. But you can enter this house, with its Scandinavian furniture and large windows on a certain steep, serpentine street in a hot summer in the Novato Hills.

Welcome! Make yourself at home!

I love place. I want my reader to BE THERE, smelling the tart eucalyptus sap, OR listening to the mournful strains of a duduk emanating from the walls, OR feeling the rain on their skin as they witness two hawks soar, like a couple, over the fields. Specific, original details awaken your imagination, allowing you, the reader, to fully inhabit the three-dimensional world of the story.

Each of the stories in The Man with Eight Pairs of Legs is irrevocably embedded in the places where they occur. Whether it is a parish in New Orleans, the red-light district of Bangkok, a high desert Colorado town teeming with prisons and churches; or smaller places like a dying man’s studio apartment, a main hall closet crammed with unopened packages, or a bathroom moist with steam, each specific setting plays an essential role in the development, meaning, and mood of its story, impacting the characters moment to moment.

In the title story, the incredible beauty of the Royal Gorge is juxtaposed with both the beauty and ugliness of technology. Time itself becomes a key element, as the suffering of the two main characters, the angst of teenagers, and even prison sentences are measured against geologic time.

After last call, [Harriet] expected [Callahan] to vanish, but he followed her on his motorcycle, eerie in her taillights, past the soaring pylons of Royal Gorge Bridge – its multi-strand cables edged with snow – and out into the prairie.

FINAL SCENE: Before turning west onto Highway 50, Callahan pulled into Royal Gorge Bridge look-out, setting his boots down so they could take in the view. A few tourists were snapping photos. The 1,260-foot bridge looked white in the midday sunlight, its giant aluminum chains slung between castellated steel girders, marring the natural landscape, but beautiful, too, even exquisite, the Arkansas River a thousand feet below. Its construction in 1929 had seemed an impossible feat and yet here it was, the tallest suspension bridge in the world, linking what had taken three million years to sever.

(The Man with Eight Pairs of Legs)

In “Thunder in Illinois,” the main character, Mr. Evans, simultaneously lives in two worlds, which he struggles to balance: a small town south of Chicago bordered by cornfields, and the loud, lively streets of Bangkok in the 1970s.

Outside in the dusk, two grinning boys came up for air after a dive from a rickety bridge into the klong, which smelled faintly of petroleum and rotting fish. After a sweltering day of sellers bargaining from their boats, the bitter-sweet scent of sun-drenched mangos and durian still lingered. In spare English, Vilai explained to Mr. Evans that it was Loy Krathong, the annual Thai full moon celebration in honor of the Mother of Water…Hundreds of tiny floating baskets, each one shaped from a banana leaf and lit with a single candle, sailed up and down the klong. Mr. Evans laughed with uncustomary ease, but all at once Vilai stopped talking. The baskets had clustered along the klong’s borders, some invisible current pushing them against its walls. They skittered like manic water bugs. One by one, their flames went out. (Thunder in Illinois)

In “Nightlight,” there are three separate and very important settings, all of which impinge on the life of Reiner, the main character, and matter to him deeply.

ADJOINING EDWARDIANS IN SAN FRANCISCO: Now the wind stung his face and cut at his neck. Stepping back, he was struck by the fairy tale quality of their two identically constructed facades, his and the old widow’s, the one tidy and brightly trimmed, the other in near ruin. He tried thrusting the screwdriver in at different angles, but the bolt refused to budge. In the distance, St. Peter’s bells rang out more times than there were hours on a clock. Beth and six-year-old Marlowe had just headed there for Sunday Mass, the two of them skipping down the sidewalk in their dress-up coats.

He glanced toward the street, quickly scanning the rows of prim San Francisco Edwardians on either side before heaving his bulk against his neighbor’s front door. It jerked open a few inches and stopped short. Reiner squeezed his head in. The living room was crammed floor to ceiling with stacks of moldy newspapers, unidentifiable items in plastic bags, a clutter of gutted cardboard boxes. Everywhere the black confetti of mice. (Nightlight)

THE RHEINHESSEN IN GERMANY: Reiner, himself, had departed the family farm at seventeen. He’d plowed his father’s two hectares of sugar beets one last time, steering the bright green tractor in large concentric squares at dusk, the light shifting indelibly until, by the time he’d worked the field to the center, the entire world was dark. There, under the first few stars, he had felt as if he had already left it all behind: the fermenting air; the clean horizons; his mother’s lingonberry pie; his father’s twinkling, circumspect eyes, feet up in front of the television; his glum sister. (Nightlight)

THE HOVEL IN THE BASEMENT APARTMENT NEXT DOOR. Wind shoved a regiment of fog over the city, everything the ocean didn’t want. [Reiner] descended the dark stairs, scaled the fence, and hesitated at the threshold to Federico’s encampment, unsure what he would find, prophet or scoundrel, before pushing open the door. Federico was sprawled on the cement floor among candy wrappers, plastic water bottles, blackened bottle caps, an old tire. Moth-eaten blankets lay crumpled next to him along with a handful of hardcover books.

“What a hell hole,” Reiner said. The ceiling was low, the walls damp; the air smelled of burnt milk. (Nightlight)

I will leave you with one last example from “The Hermit’s Tattoo” in which a raging wild fire in the Sonoma Hills forces a lone monk to evacuate from his rustic hermitage.

The backroad that October night blistered with heat and smoke as it curved through the valley like a river. Behind me, the place of my silence. A place that was never itself silent. Nor had I been able to make it so. When I gardened or prayed or drew water from the well, I’d hear the wing-wind of the two resident ravens and their gurgling deep-throated calls, the rapid knocking of woodpeckers ramming thumb-sized holes into the lone telephone pole, the twitter of swallows and sparrows in the blue oak limbs. At dusk, the bullfrogs belched out their pain and lust like drunk bastards on a street corner. After my evening meal, I often sat on my deck and listened to their existential hollering: I’m here, I’m here, I’m here. Their insistence felt brutal. But I could imagine a time when they would not be here, nor would anything that survives on chlorophyll or a heartbeat. The land was loquacious. But not that night.

(The Hermit’s Tattoo)

EVERY SETTING IN THE MAN WITH EIGHT PAIRS OF LEGS MATTERS. JUST AS EACH STORY IS, I HOPE, A FULLY ENGAGING JOURNEY FOR YOU, THE READER.