The Animated Role of Inanimate Objects in The Man with Eight Pairs of Legs

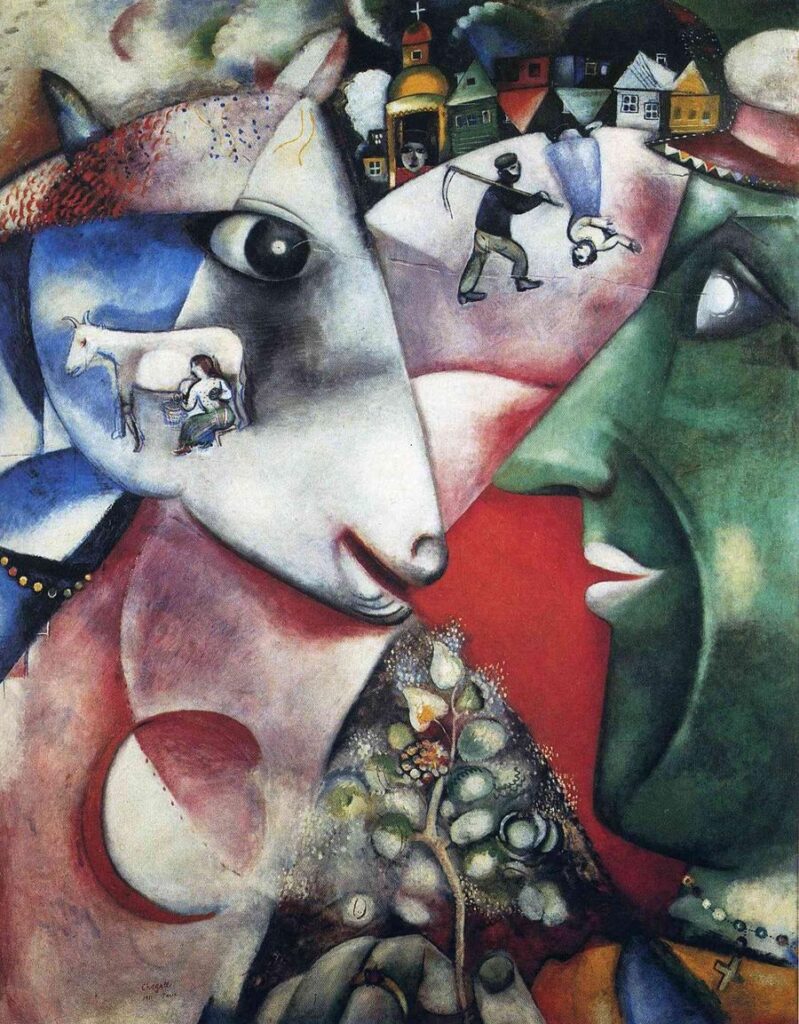

I am a visual thinker. A sensual woman. A sensory woman. What I see is important to me. What I touch, the texture. What I smell. What I hear. Light and the way light alters the density of things as they appear, muting or brightening color, shading, creating atmosphere and mood. When I first imagined a cover for my book, I thought of the Russian painter, Marc Chagall, an assemblage of overlapping images from the eight stories in my collection:

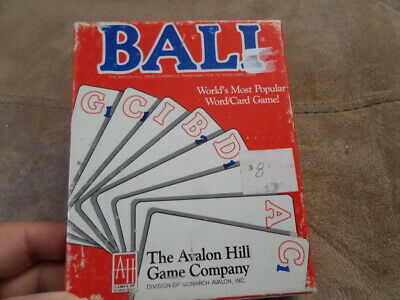

Bali cards turned face up with letters on them (“Thunder in Illinois”); Martin Heidegger’s philosophical classic Sein und Zeit, or a dark house with one small light (“Nightlight”); the bridge over the Royal Gorge (“The Man with Eight Pairs of Legs”); Llyn’s blue painting with a speck of red in the top right corner (“Triptych”); a few felled trees (“Tasmanians”); a cupcake in the gutter, or lemons spilled onto sunlit grass (“Overture”); a fire coming over the hills (“The Hermit’s Tattoo”).

Images create the fullness of place, a fictional world the reader can inhabit. But the author’s camera can also light upon particular objects – a kind of inventory in each story – each object potent beyond measure.

Today, I would like to amplify the importance of inanimate objects in my fiction. Take note: I am not talking about just any old object, but an object upon which the entire story turns. Without these objects, there would be no story!! Like those Bali cards, or Sein und Zeit signed by the author, or that blue painting. There are other significant objects in my collection: eight pairs of prosthetics, an Armenian duduk, a silver flute. Fire, I have realized, is an essential inanimate element in two of the stories, and thus carries even more weight for the collection. In fact, now that I think about it, each story, in its own way, courts danger.

RESONANT OBJECTS IN MY COLLECTION

Prosthetics are potent objects in The Man with Eight Pairs of Legs, the title story, both for Callahan, the new guy in town, and Harriet, the tall, thin maverick high school teacher he meets at Lola’s Saloon on Main Street in a small Colorado town. For Callahan, a double-amputee, they are life-changing.

For Harriet, they are, at first, horrifying; then thrilling works of art; then envied, dreamt about, and, ultimately, irrationally desired. Inventory in fiction is never random. The object must be essential to the story and deepen its meaning. In this case, the presence of Callahan’s high tech legs – in relation to Harriet’s overly long and awkward human legs – raises questions about aging, mortality, and the allure of body enhancements. The story asks, finally, what we might be willing to do – no matter how extreme – for love.

In Thunder in Illinois, Mr. and Mrs. Evans play three games of Bali, a word game with cards, on a Saturday evening. They have been playing this game regularly throughout their entire forty-year marriage and keeping their cumulative scores. Mr. Evans has won individual games, but has never taken the cumulative lead. Tonight, he says to his wife, “I can die as soon as I get more points than you, dear. I’m just a hair’s breadth away.” His body is a map of bruises, but he decides to keep his recent prognosis under wraps. As they sit at their old teak table playing the game, their entire marriage is revealed: their work and children, their intimacy and philandering, their competing intelligences and troubled love. Who will win? And who will die, we wonder, as they play the last game of the evening on their patio, under an array of shooting stars?

A flute plays a pivotal role in Overture. Margie, trapped in an abusive relationship with Mark, loves to sing opera. In fact, she played key roles in “Carmen” and “The Magic Flute” while still in high school. Her fifth grade son, Steve, plays the flute in his elementary school orchestra where he will be playing a child’s version of the “Overture to Norma” at a school assembly tomorrow night. Margie has been watching Steve assemble and dismantle his flute every night after he practices his part. She wants to go, but Mark doesn’t ever allow her to leave the house. Unexpectedly, the next night, he does. They will all go! Tonight, in the dark, Margie tells us, I hear Stevie’s familiar breath inside the notes. At first, they waver like shy children, then find their way, beautiful and pure. In the final scene, the flute, innocently left on a chair, is transformed into something that just might save them.

In Nightlight, Reiner, who is now an engineer, married, and with a four-year-old son, longs for his younger days when his mind thrived on philosophical ideas, those fertile years when the words of the great German poets took his breath away. He treasures his signed copy of Sein und Zeit (Being and Time) by Heidegger gifted to him by his high school philosophy teacher. But when he meets Federico, the young heroin addict squatting in the abandoned house next door, Federico covets Reiner’s precious book, and much more. Federico, unburdened by marriage and work, lives and breathes the words of the same philosophers and poets Reiner once loved. In this story, Sein und Zeit is not just an object: it becomes a symbol for everything Reiner has lost. Will he give it up? In fact, how much is he willing to lose to keep his mind mistress next door?

Objects are central to the plot in Tasmanians. Without them, there would be no story! Mariam, an Armenian-American woman in her thirties, has moved north as far as possible from her Armenian grandmother, Osan, who lives with Mariam’s mother in Burbank. But Osan can’t stop sending her objects from the old world of Anatolia: Christian reliquaries, ceramic oil lamps, a collection of coins, some dating back to the Ararat. It is as if they have hearts. Mariam hears them beating in the recesses of the closet where she has stuffed them. The story intensifies when Osan sends a duduk, the ancient Armenian flute that belonged to Mariam’s dead father. Mariam starts to hear its mournful tunes in the eucalyptus groves outside her bedroom, then inside the walls of her house. These songs do not belong to her. Or do they? Will her appreciation of what the duduk signifies, personally and historically, come too late?

In the last story of this collection, Triptych, Llyn, a single mother and artist living in San Francisco during the early days of the AIDS epidemic, is working on a series of paintings, her Arctic Series, in which she is coming to terms with the loss of thousands of impoverished immigrants attempting to cross the Atlantic from Britain to the US in the 1800s by ship. Her own great great grandparents, and all but one of their children, drowned on their way to America. After finishing art school, I washed dishes by day and painted that one blue acre at night. Llyn is so obsessed with her painting – and what she imagines lies below the surface of her brush strokes – that she neglects her infant, Cash, and relies on her neighbor Grady, who is dying of AIDS, to take care of him. When Llyn finally manages to complete the final painting of the series, cutting the barn-door-sized painting into a triptych, the three characters’ trajectories converge in a precarious state of grace.

Objects are just one entry point into these multi-faceted stories. Other entry points are character; tone; language (and its music); structure (tectonics); action; narrative arc; layers of meaning emanating from echoes/rhymes of image or idea; theme; time; and place. Still, inanimate objects have their special place in fiction – each one with its undeniable it-ness, its volume and weight. Listen closely and you will hear a concertina vibrating at its heart.